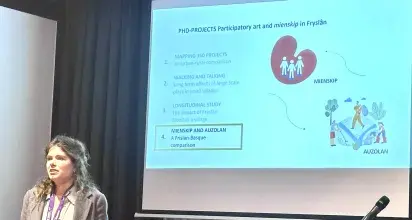

In the photo Carmen van Bruggen, University of Groningen, Faculty of Spatial Sciences, during her presentation.

- Blog

Euskampus in the 3rd conference on Frisian Humanities

75 presentations in the field of Frisian studies at the 3rd Conference on Frisian Humanities.

Euskampus participates in the 3rd Conference on Frisian Humanities sharing progress about the linguistic diversity management in Euskampus Bordeaux Campus.

How can we grow awareness of our linguistic diversity in international projects? How do we manage giving breathing spaces for Basque as a minority language in contact with hegemonic languages such as Spanish or French in contact also with lingua francas like English? What are our language practices in the cross-border scenario of New Aquitaine-Euskadi-Nafarroa? These are some of the issues Euskampus shared at the conference on Frisian Humanities that took place last 12-14 November at Leeuwarden, The Netherlands.

The conference was oganized by the University of Groningen, Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning, Leeuwarden (NL), in collaboration with Fryske Academy, amongst others. Researchers coming from Spain, Germany, Norway, Luxembourg, USA, Belgium, affiliated with more than 35 universities participated in this enriching conference producing no fewer than 59 research lectures, 1 discussion panel and 16 scientific posters.

The conference that lasted 3 days, was opened by the mayor of the town, Sybrand van Haersma Buma who mentioned in his talk how “Leeuwarden was the European capital of culture in 2018, and with 130.000 inhabitants, is proud of their own language, Frisian, in a globalized world, because language is at the heart, it carries our identity, and stories are told in Frisian”.

Many languages in a plural Europe

The conference also highlighted the importance of cooperation among small nations—building mutual understanding as a foundation for collaboration. In the Netherlands, around 450,000 people speak Frisian, one of the country’s four minority languages. Participants reflected on how languages are perceived as separate in people’s minds and questioned the extent of this division.

In a global Europe with 24 official languages and 80 regional or minority languages, 10% of the EU population—approximately 80 million people—speaks a minority language. These figures speak for themselves.

There are other minority languages spoken in the country such as Linbourgish, Low Saxon or Gronings. However, these do not have the status as Frisian does, and curiously enough, although Linbourgish has more speakers than Frisian, there are differences between the scope this language has in comparison with Frisian.

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

Special attention was given to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, highlighted during the conference, which is a key legal instrument for safeguarding vulnerable languages. Its overarching goal is to protect and promote these languages, fostering multilingual societies and raising language awareness. While some countries sign the Charter, others go further by ratifying it—a step that significantly strengthens the language rights granted to minority communities.

Adopted by the Council of Europe, the Charter seeks to ensure the use of traditional regional or minority languages across all areas of public life. These languages form an integral part of Europe’s cultural heritage, and their protection contributes to building a Europe rooted in democracy and cultural diversity. Implementation of the Charter is overseen by a committee of independent experts.

In the fruitful encounter, attended by more than 200 people, Basque, Welsh, Sorbian, Irish-Gaelic were some of the languages compared. Interesting reflections were made in terms of language rights and language evolution in their respective countries.

Lingua franca versus plurilingualilsm

Caterina Sugranyes, from Universitat Ramón Llull, Barcelona (in the picture) gave a passionate keynote lecture titled ‘”Embracing a positive approach to promote effective plurilingual teaching through plurilingual wellbeing’. She mentioned some of the characteristics embedded in plurilingual wellbeing: feeling natural using your linguistic repertoire, grow language awareness, language visibility, positive plurilingual approcah to learning and teaching, positive response, openness to other languages, feeling valuable, also feeling pride and satifaction when one realises own’s language abilities.

Her presentation explored the relationship between teachers’ views of language, their language repertoires, and how they teach and handle plurilingualism in the classroom. It does so by addressing the concept of plurilingual wellbeing (Sugranyes et al., 2024), which is defined as being aware and valuing one’s own language repertoire and feeling comfortable with using it in a variety of contexts.

Plurilingual wellbeing embraces a positive approach to teaching (Mercer, 2021) which stems from research on teacher wellbeing, language awareness and plurilingual identity and it understands how teachers navigate their own plurilingualism and that of learners.

Itxaso Etxebarria, from Euskampus (in the picture), shared the progress being done in the cross-borders campus in matters of multilingualism, where we manage the language diversity of the 4 languages that coexist. That is to say: Euskara as a minority language in need of protection and breathing spaces, French and Spanish as hegemonic and dominant languages and English as a lingua franca.

What happens when we adopt English as the sole vehicular language? Malaise for not being able to express yourself fully, lack of emotional involvement, loss of identity , are some of the drawbacks of not being able to use your own language. In this globalized world , the dilemma between internationalizing our university but staying true to your origins often leads us to choose between using a minority language or a dominant one, or even a lingua franca such as English when it comes to consider the impact we want to make.

In order to resolve this, some language dynamics are observed during the moments of international interaction in cross-borders projects such as translanguaging, receptive multilingualism, code-switching, whispering interpretation. All of these used to deal with this rich language diversity.

Social parallelisms between Frysland and the Basque Country

To close the conference, one of the final lectures was delivered by Carmen van Bruggen from the University of Groningen’s Faculty of Spatial Sciences. In her talk on how geography shapes social relations, she drew a fascinating comparison between the Dutch concept of mienskip—a Frisian term meaning “community,” but encompassing much more, such as interconnectedness, trust, and solidarity, rooted in the centuries-old Dutch struggle against water—and the Basque practice of auzolana, which refers to collaborative work for the common good, where neighbors periodically join forces on shared projects.

Her research, which explores the intersections of art, culture, and geography, revealed that in small rural areas—such as the more than 220 villages in Fryslân with fewer than 500 inhabitants—communities actively cooperate for collective benefit. Interestingly, she found that the more rural the setting, the higher the number of volunteers willing to contribute to these efforts.

This spirit resonates strongly with the cooperative ethos of the Basque Country—from auzolan to modern cooperativism—where collective action is directed toward the common good of the territory. It reflects a sense of community and solidarity that drives genuine societal impact.

There are clear parallels between this Dutch tradition and the Basque experience, where minority languages, as carriers of social identity, shape behaviors and foster connections, enabling communities to co-create for the common good.

The full programme can be found here, the Book of Abstracts here.

More information: Website Conference on Frisian Humanities

Subscribe to Newskampus

And get our latest news in your inbox.